- Home

- Jeremy Musson

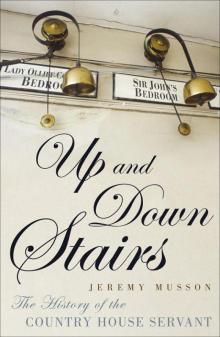

Up and Down Stairs

Up and Down Stairs Read online

Also by Jeremy Musson

The English Manor House

100 Period Details: Plasterwork

How to Read a Country House

The Country Houses of Sir John Vanbrugh

Up and Down Stairs

The History of the Country House Servant

JEREMY MUSSON

www.johnmurray.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by John Murray (Publishers)

An Hachette UK company

© Jeremy Musson 2009

The right of Jeremy Musson to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978-1-84854-387-4

Book ISBN 978-0-7195-9730-5

John Murray (Publishers)

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.johnmurray.co.uk

To my amazing mother, Elizabeth (1942–2009)

Contents

Introduction

1. The Visible and Glorious Household

From the later Middle Ages to the end of the Sixteenth Century

2. The Beginning of the Back Stairs and the Servants’ Hall

The Seventeenth Century

3. The Household in the Age of Conspicuous

Consumption

The Eighteenth Century

4. Behind the Green Baize Door

The Eighteenth Century

5. The Apogee

The Nineteenth Century

6. Moving Up or Moving On

The Nineteenth Century

7. In Retreat from a Golden Age

The first half of the Twentieth century

8. Staying On: A Changing World

The later Twentieth Century

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography and Sources

Introduction

A SERVANT, ACCORDING to Dr Johnson in his famous Dictionary of 1755, was ‘one who attends another, and acts at his command – the correlative of master’. It is curious to think that, until the 1950s, the very term was as commonplace as any word relating to housekeeping among the upper and middle classes. Yet by the 1960s and 1970s, the word had virtually disappeared from everyday use.

Johnson’s definition is essentially repeated by The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary of 1979 but also gives a second meaning – originating from late medieval English – ‘One is who is under the obligation to render certain services to, and obey the orders of a person, or body of persons, in return for wages or salary.’1 The word ‘servant’ thus traditionally encompassed the status of a trades’ apprentice to his master, and was often extended to other labourers in employment. The term domestic servant seems to have emerged to distinguish it from the increasing significance of the ‘civil’ servant, someone who worked for the government.

For those who love looking around country houses, the servant should be regarded as an indivisible part of the story. Like great machines, these houses combined public and private functions, as places of residence and hospitality, as well as of political and estate administration. They were built not only for the occupation of a landowning family but also had to accommodate a large body of servants to run it, whose duties included not only providing food, heat and light but the maintenance of precious contents and furnishings that needed constant attention. This book will focus on the domestic servant of the larger country house, rather than of the town house or the middle-class household.2

The first chapter begins in the 1400s, and after 1600 each century has a chapter to itself. The two that cover the period up to 1700 are naturally more of an overview, fleshing out those who would have worked in a large landowner’s household, spelling out those lives and duties which can be deduced from limited available sources. From the seventeenth century, through memoirs and letters such as those of the Verney family, and books by authors such as Hannah Wolley, we start to get a much more vivid sense of connection with the complex life stories and responsibilities of country-house servants.

The chapters on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries focus closely on the different roles and responsibilities of servants, identified via treatises, wage lists and numerous household regulations, alongside published and unpublished diaries and letters, of both employed and employer. From the twentieth century to the present day, the focus is much more on actual memoirs, including interviews conducted with a sample of current and retired domestic and estate staff, as well as with country-house owners from all over the British Isles. These living memories give us an insight into the way big houses functioned in the past and continue to do so today. These recollections often supply a contact with the interwar years, when the senior servants of the time had received their training in the Edwardian period.

One of the overriding themes is the changing role of the sexes in service. Medieval and Tudor households, for instance, were principally staffed by men – even in the kitchens. From the late seventeenth century, however, female staff began to outnumber the males, and the female housekeeper took on key management duties of overseeing the female staff, as the mistress by proxy. Cleaning duties, the kitchen, the laundry and the dairy became largely the preserve of women, which perhaps, despite the intervention of technology, the two former still remain today.

There is also the distinct issue of both the visible and the invisible household. In medieval and Tudor times, establishments were deeply ingrained with ideals of servants being on display and public hospitality, but in the seventeenth century an increasing desire for privacy led to a separation of lower servants from the public spaces occupied by the landowner’s family. This was achieved by means of architectural divisions and household management. It is at this point that separate staircases for servants and separate servants’ dining halls come into being and the bells to summon servants begin to appear.

Menservants, especially footmen, were the subject of taxation from 1777 until the 1930s, producing the distinct oddity, found in some country-house archives, of printed licences for ‘dogs, menservants and armorial bearings’.3 But while footmen added a glorious presence in their richly coloured uniforms, known as liveries, and their powdered wigs, their duties were practical too, as bodyguards and attendants on coaches, or as carriers of messages. Their daytime manual duties, such as cleaning silver and fine glass, were overseen by the butler.

The increasing specialisation of domestic service, with certain duties attached to dedicated zones within the house and within the service areas, is a defining feature of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the management and hospitality of country houses seems to have reached a pitch that was much admired by international visitors. The start of the First World War marked an inevitable decline in numbers of such large household staffs (for economic reasons if no other), and the Second World War was an even more significant watershed.

The apparent evaporation, in the later twentieth century, of the servant-supported, country-house way of life, which had defined the image of the British nation in the previous centuries, is, of course, a subject of fascination in itself. But was it quite so clear cut? Some country houses maintained surprisingly large staffs right up until recent times, at least until the 1960s, and some beyond. The dramatic image of the funeral procession in May 2004 for Andrew Cavendish, the 11th Duke of Devonshire, reminds us that not only are some country houses still well staffed b

ut that they and their owners continue to be served by dedicated and skilled people who take the greatest pride in their roles.4

It is important to remember that in the Middle Ages, senior household officers, themselves minor landowners, would not have thought twice about being called a servant to a noble lord. The word had none of the social stigma associated with it in the early and mid twentieth century. Incidentally, until the eighteenth century, the word ‘family’ was used interchangeably with what we understand as a ‘household’ to cover all the persons who lived under one roof. It thus embraced all live-in domestic servants, although it was used in the legal, Latin sense of meaning everyone who came under the authority of the head of the house – the paterfamilias.5

From the late seventeenth century onwards, servants were more likely to seek ways of moving on, either to new and better jobs, or sometimes out of domestic service altogether,6 although the word ‘servant’ continued to be applied to men and women of considerable ability and experience, such as stewards, French chefs, butlers and housekeepers. Moreover, the world of domestic service was itself subject to many distinct levels of internal hierarchy, reflected in areas such as address, dress, meals and accommodation. The more senior the servant, the better the status and the related rewards. Positions that offered fringe benefits could be particularly attractive.

In 1825, a footman could earn £24 a year and he also received free accommodation, clothes and much of his food (and might possibly get tips as well). This compares well to the average agricultural wage of around 11 shillings a week, with some upward variation at harvest, out of which workers would have to feed and clothe themselves and their families, as well as pay rent.7

In the 1870s, a skilled French chef in a country house could earn as much as £120 a year while an experienced butler could hope to earn around £80. Even a young footman might be paid £28 annually plus food, accommodation, and an allowance for clothing and hair powder. This puts many country-house servants into quite a different league from the worst-paid industrial workers of the time. One survey of labour in Salford in the 1880s suggested that over 60 per cent of industrial workers lived in near poverty, earning less than 4 shillings a week, from which they had to find shelter, clothing and food.8

One key theme that emerges across the centuries is the mutual interdependence of the country-house world. Many country-house servants served the same families for most of their working lives, and there are numerous examples of deep attachment, loyalty and mutual respect. A particularly vivid and well-celebrated example of this is illustrated by the series of portraits, commissioned by the Yorke family during the eighteenth century, of their servants at Erddig, near Wrexham (now owned by the National Trust), and the doggerel verses that described and celebrated their roles in the household – they famously commissioned more portraits of their servants than of their own family.9 Bequests to servants can be traced from the Middle Ages onwards, recognising the trust and loyalty of individuals, and intended to help make secure their old age.

In the post-medieval world, the changing perception of individual liberty led to a continual re-examination of the role and profession of the residential domestic servant, whose regimented lives and dependent positions ensured the existence of the country house. The challenges to landed power, the changes brought by the industrial revolution and a new political idealism all had their impact on the way servants saw their work. By the early nineteenth century, the word itself had begun to take on more negative associations, of subservience to an inflexible class system.

For instance, William Tayler, an experienced footman, wrote in his diary in 1837: ‘The life of a gentleman’s servant is something like that of a bird shut up in cage. The bird is well housed and well fed, but deprived of liberty, and liberty is the dearest and sweetes[t] object of all Englishmen. Therefore I would rather be like the sparrow or lark, have less of housing and feeding and rather more liberty.’10 But elsewhere he reflected that he could not understand how tradesmen and mechanics could sneer at the domestic servant, as, by virtue of his exposure to more variety, richer experience and greater mobility, he saw so much more of the world than they did.

Whatever modern observers feel about the idea of domestic service, there is no doubt that it was defining feature of country-house life for centuries, and these pages will reveal something of the extraordinary range of men and women on their staffs, whose contribution should be valued in its own right.

The story of the country-house servant is a very human one, as varied as any other working career in agriculture and industry. However, they are also unusual in that, unlike the vast majority who worked as single-handed, general domestics in middle-class town houses, they had more opportunities for career progression and social life.

Above all, the story of a country-house servant on a landed estate of any size was always one of a community of people with closely inter-related careers and lives, often at the centre of a self-sufficient and insulated environment of an agricultural estate.11 The statistician W.T. Lanyon noted in 1908 of one country-house environment: ‘the premises constituted a settlement as large as a small village: carrying coals, making up fires and attending to a vast number of candles and lamps, necessitated the employment of several footmen.’12 The lives of the servants were reflected in the physical form and layout of the country house, a theme that is explored throughout this book.

Moreover, domestic servants made up the largest contingent of the dramatis personae of the country house, even if they are less well recorded in the history books than those they served. In the late Middle Ages and the Tudor period, noble households might number hundreds of menials, whereas in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries such households had reduced to between twenty-five and forty indoor servants. Often there would be an even bigger staff for the gardens and the home farm. Even in living memory, until 1939, a landowning family of just six people could be looked after by a substantial resident indoor staff of around twenty.

There are no simple national statistics for people employed in domestic service in country houses alone. Nationally, larger households in the Tudor era would have accounted for several thousand souls, from higher-ranking gentleman attendants down to the boy turning the spit in the kitchen. There were probably around 1,500 great households with staffs of between 100 and 200.13

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, great country houses generally employed in the region of thirty to fifty indoor staff, and if one includes outdoor staff, of gardeners, grooms and gamekeepers, the total might reach many times that figure. The Duke of Westminster employed over 300 servants at Eaton Hall in the 1890s, while the Duke of Bridgewater retained some 500 staff at Ashridge and, indeed, was said never to refuse a request for work from a local man.

At Welbeck Abbey, in Nottinghamshire, where in 1900 the Duke of Portland employed around 320 servants, his rule was recalled as one of ‘almost feudal indisputable power’.14 Moreover, major landowners often had staff spread over two or three estates as well as a London house, although in many cases this would be a skeleton staff only, with the core skilled individuals travelling with their employers from place to place, itself a considerable logistical operation. As a result the staff of the country house was also that of the London house when in use by the landowning family.15

However, even when such households were at a peak in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the numbers of aristocratic and wealthier gentry country-house servants could not have accounted for more than 15 to 20 per cent of the national total of domestic servants.16 During that period domestic service was one of the major forms of employment. In 1851, for instance, 905,000 women and 134,000 men worked as servants. The total number nationally is thought to have been around 2 million in 1901, out of a total population of 40 million, making domestic service the largest employment for English women, and the second largest employment for all English people, male and female, after agricultural labour.17 In the census of 1911, domesti

c servants accounted for 1.3 million, outnumbering the 1.2 million in agriculture, and the 971,000 in coal mining (and, incidentally, the same number of those involved in teaching today).18

After the Second World War, the world of the country house changed out of all recognition, and the enclosed, stratified and hierarchical communities of domestic servants evaporated. Houses that must have hummed with activity, at least below stairs and behind the green baize door (invented in the eighteenth century to increase soundproofing), became quieter, emptier places, in a process that had begun back in the 1920s with increased taxation and the effects of the Great Depression.

After 1945, when their wartime use came to an end, many large country houses were not reoccupied because landowners were unable to recruit – and afford – the staff to manage them. As country houses cannot function without help, those that remained in private ownership relied, as some do today, on a loyal and dedicated staff. Whilst there are still butlers, house-managers, housekeepers and cooks, few are resident. The mid-to-late twentieth century became the era of the daily cleaner – with agency staff brought in, often on a regular basis, for larger-scale hospitality and special events.

According to Fiona Reynolds, Director-General of the National Trust, most of us in Britain – where less than a hundred years ago domestic service was still one of the largest employers – will have ancestors who were in service. This prompts our interest in the whole working of the house, its domestic spaces as well as the grand state rooms. Both have – after all – always been entirely interdependent.19

Up and Down Stairs

Up and Down Stairs