- Home

- Jeremy Musson

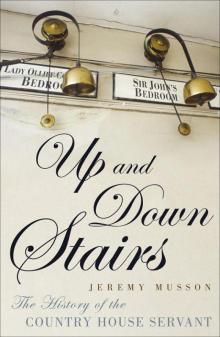

Up and Down Stairs Page 13

Up and Down Stairs Read online

Page 13

Some stewards were French, as their knowledge of French customs and manners was thought to give them a certain cachet, as well as making them useful if the family travelled on the continent.36

Under the steward, the clerk of the kitchens – a traditional role in the household – managed the needs of the kitchen, identifying what provisions were needed and ordering them, as well as drawing up menus, setting times of meals and supervising service. Thus many of the lower servants came under his control. The instructions drawn up by the 2nd Earl of Nottingham, for his clerk of kitchens at Burley on the Hill, indicate that he not only kept the keys for important provisions, but was also the primary timekeeper. He was charged to ‘Fail not to have the dinner ready by 12 of the clock and let the bell then be rung and dinner served up, likewise supper at 7.’ At Burley he was also expected to be present at service: ‘You must wait at the lower end of the Parlour table that you may be in My Lady’s eye and be directed when to go for the second course.’37

With the arrival of more specialist foreign chefs (especially French ones) and confectioners, over the century the clerk of the kitchen’s role diminished, some of his responsibilities passing to the female housekeeper. It was a position that by 1770 seems to have largely disappeared or at least become one with the role of the male cook, as suggested by wages lists such as that for Arundel Castle, with its ‘cook & clark to the kitchen’.38

Much was expected of such a person. In 1769, Bernard Clermont wrote in The Professed Cook that a cook ‘should be a man of thorough knowledge in his profession, capable of forming a bill of fare, and dressing it when approved of. He should be well versed in what is a sufficiency for the support of the family which he is to provide for, be they more or less in number.’39

French chefs were popular. In the 1720s the Earl of Leicester recruited his cook, Monsieur Norreaux, directly from Paris and paid him 60 guineas per annum, together with a French under-cook, Jean-Baptiste. English male cooks might find opportunities for acquiring continental culinary arts, as did William Verral, who learnt them from the French cook of the Duke of Newcastle early in the eighteenth century. The male cook was often the highest-paid servant after the steward.40

The Duc de La Rochefoucauld wrote in the 1780s: ‘English cooks are not very clever folk, and even in the best houses one fares very ill. The height of luxury is to have a Frenchman, but few people can afford the expense.’41 On the other hand, French cooks were thought to have ideas above their station. In the London Magazine of 1779, James Boswell wrote that ‘A French cook’s notion of his own consequence is prodigious,’ and went on to recount the story told him by the British ambassador to Spain, Sir Benjamin Keen. When interviewing French cooks to work for him, Keen asked one whether he had ever cooked any magnificent dishes. The reply came: ‘Monsieur, j’ai accommodé un dîner qui faisait trembler toute la France.’42

The number of French chefs increased in the final years of the eighteenth century when the French Revolution drove many across the Channel to Britain. Famously Mr Ude, former cook to Louis XVI, was hired by the Earl of Sefton with the huge annual salary of 300 guineas. In his book he argued that a cook of his fame should never be regarded merely as a servant.43

By the beginning of the nineteenth century there could well have been between 400 and 500 great families employing a French or foreign chef who would travel back and forth from London to the country alongside the family.44 It is worth noting that in the course of the eighteenth century, the time of the main meal of the day shifted from lunchtime to the evening. In the early eighteenth century, the essayist Richard Steele wrote: ‘In my memory the dinner hour has crept from 12 o’clock to 3.’ By 1800, dinner was usually served anywhere between five and seven.45

The valet de chambre or valet, reporting to the steward, was a key senior male servant whose chief responsibility was the appearance, dress and presentation of his master. As with John Macdonald, a valet would also need to be an accomplished barber. He would be in continual attendance on his master, accompanying him on all his travels, reflecting glory and making himself indispensable. John Moore wrote disparagingly of the Bertie Woosters of his day in 1780 that:

many of our acquaintances seem absolutely incapable of motion, till they have been wound up by their valets. They have no more use of their hands for any office about their own persons, than if they were paralytic. At night they must wait for their servants, before they can undress themselves, and go to bed: In the morning, if the valet happens to be out of the way, the master must remain helpless and sprawling in bed, like a turtle on its back upon the kitchen table of an alderman.46

Not a liveried servant, the valet would normally be dressed in the manner of a gentleman, with appropriate manners and deportment. Anthony Heasel in the Servants’ Book of Knowledge (1733) observed that ‘A valet must be master of every sort of politeness, to which he must take care to accustom himself without stiffness or affectation.’ Valets were also usually expected to speak some French.47

The butler, who had been a relatively minor figure up until the seventeenth century, becomes a grander fixture in the household of the eighteenth. In the wealthier establishment a butler reported to a steward, managed the footmen and supervised the waiting at table. As well as having control of the wine cellar, the butler usually had the immediate care of the plate (that is, silver) and fine glass, overseeing the cleaning, storage and security of these valuable items in his headquarters, or butler’s pantry. In the Servants’ Book of Knowledge Anthony Heasel warns butlers: ‘As all the plate will be committed to your care, never suffer strangers to come into the place where it is kept; nor let the place be ever left open.’48

A butler in a more modest-sized country house must have a wide variety of talents. One advertisement for a post in Suffolk in 1775 sought ‘a Butler that can shoot and shave well’.49 In 1797, Sir William Heathcote of Hursley indicated that his butler ‘Must understand Brewing & Management of the Cellar, Clean his own plate, and do all his own work, as no under Butler will be kept.’ Also, ‘he Must see all the Family [the servants] go to bed before him, & see every door and window Made fast & secure.’ He was expected to answer bells at any time during the day.50

The regulations of the household at Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire, in the same decade, describe the roles of steward and butler combined in one man:

The House Steward & Butler is ordered to see weighed, & enter in a book every morning all descriptions of provisions that are brought to the house; and all persons whatsoever, bringing meat fowls of all sorts, Game, Fish, eggs for Kitchen use . . . are to make the same known to the House Steward & Butler, that he may make his entries. In like manner, coals, Oils & Wax candles are to duly entered into his book, on the day of their arrival.51

There are phrases in Anthony Heasel’s book of advice to servants that are direct echoes of the treatise by John Russell, writing of the medieval household: ‘Take great care of your wine and other liquors, not only to keep them in good order, but likewise to prevent their being embezzled, or given away to any person besides those who have a right to them according to your instructions.’52

In medieval times the groom of the chambers was a young male assistant to the chamberlain. By the eighteenth century this ancient title had come to apply to a senior manservant, who dined with other senior servants such as the head cook and butler but, unlike them, wore livery. His principal duties were apparently to oversee the presentation and cleaning of the main reception rooms. Among other things, he had to ensure that the ornate furniture was returned to its proper place after it had been used by visitors and that tables were in order. He literally dressed the rooms.

The 2nd Earl of Nottingham at Burley had a long list of the duties of his groom of the chambers that began with: ‘You must be careful of the furniture, brushing and cleaning every morning that w[hi]ch is [in] constant use, and the rest also once in the week or oftener if need be.’ His other duties related to the maintenance of fires, the replacement

of candles and closing of windows and shutters, as well as the care and presentation of the chapel.53

The groom of the chambers usually had the key role of greeting and announcing visitors, then directing them to their proper rooms, ensuring that they had everything required for their comfort.54 Some grooms of the chambers were even trained in upholstery.55 This individual was certainly among the servants who received a share of the fees when paying visitors were shown round a house. This sometimes led to rivalry with the housekeeper, as apparently happened at Cannons, the home of the Duke of Chandos.56

Below the footmen, there were clearly often additional men and boys (by the nineteenth century known as ‘odd men’) who could help with dirtier, more manual jobs, including cleaning drains and gutters, and clearing away slops. One unusually titled junior male servant is worth noting here, although he is one of a kind. ‘The Rubber’ is referred to in the early-eighteenth-century ‘General Instructions’ drawn up for the household at Boughton in Northamptonshire. ‘He is under the Direction of the Hous[e]keeper to Dry rub the Floors in the House, to fetch and carry Water for the Hous[e]maids for washing the house, to fetch and carry the Ladders and assist upon the Ladders in Washing the Wainscoat and Cornishes when ordered.’ He was also responsible for lighting the fire in the steward’s hall, waiting at table there, and helping with carrying in the food.57

The female indoor staff were by this time very much under the leadership of the housekeeper. This increasingly essential figure managed the linen, the cleaning of rooms and, if there were no clerk of the kitchen or male cook, the kitchen. Below her would be the female cook, followed by a number of chambermaids, housemaids, laundrymaids, and kitchen and scullery maids. Those housekeeping duties that in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries had been managed by the mistresses of the household were by now largely handed over to a trusted housekeeper. Many of them seem to have done long service, as did Mrs Garnett at Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, who ran the house for over forty years.58

One former housekeeper, Elizabeth Raffald, who had worked for Lady Elizabeth Warburton, put together over 800 recipes for pickling, potting, wines, vinegars, ‘catchups’, and distilling, which were published as The Experienced English Housewife in 1769. This entrepreneurial lady also set up an early registry for servants in Manchester, before running an inn, a profession to which many retired senior servants devoted their savings and energies.59

At the beginning of the century, in gentry households at least, housekeepers might well be a family relative of some sort. In 1792, Francis Grose, looking back in time, wrote: ‘When I was a young man there existed in the families of . . . the rank of gentlemen, a certain antiquated female, either maiden or widow, commonly an aunt or cousin.’ He recalled: ‘By the side of this good old lady jingled a bunch of keys, securing in different closets and corner cupboards all sorts of cordial waters’ as well as: ‘washes for the complexion . . . a rich, seed cake, a number of pots of currant jelly and raspberry jam.’60 As the housekeeper’s room became a place where expensive foodstuffs would be stored under lock and key, the individuals themselves were often depicted in paintings with a large bunch of keys at their waists.

They were more likely to have been a senior indoor maid, cook, or nurse. In the mid eighteenth century, one dairymaid, Sarah Staniforth, unusually managed to work her way up the ladder. After joining the staff of Holkham Hall in 1731, she became housemaid in 1741 and housekeeper in 1750. In this post she was paid £20 a year and remained there until her death in 1772. In her will she left over £1,000.61

In grander country houses, a female might be an under-cook to a chef, but in many houses the sole and chief cook might be a woman. While (male) French chefs were popular with the aristocracy, there were many, like Hannah Glasse, who thought their worth exaggerated. She observed in The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747) that ‘if gentlemen will have French cooks they must pay for French tricks’. Her book was intended to instruct kitchenmaids in basic cookery, thus reducing the need for the lady of the house to instruct them herself.62

Recruiting a cook could obviously be a challenge. Lady Grisell Baillie’s household accounts for 1717 show that one cook arrived on 1 February and stayed just two weeks, whilst the next candidate spent only one night in the house. It was not until July that Lady Grisell found a cook who was content with the situation. Anne Griffith was to get ‘£7 a year’ and ‘£8 if she does well’.63 Mrs Delaney, looking for a cook for her country house, regretted the one that got away: ‘the cook I gave an account of who was a most desirable servant, said she could not live in the country it was so melancholy.’64

In The Housekeeping Book of Susannah Whatman (1776), the author stresses how important it was for the mistress, or her housekeeper, to lay down the rules of the house and the kitchen to any new cook: ‘When a new Cook comes, much attention is necessary till she is got into all the common rules and observances . . . filling the hog pails, washing up the butter dish, salad bowl etc.: giving an eye to the scowering of saucepans by the Dairy-maid, preserving the water in which the meat is boiled for broth: keeping all her places clean: managing her fire and her kitchen linen.’65

Mrs Purefoy, a gentry lady running her small country house, wrote to one candidate cook, Betty Hows, offering to train her in the finer points of her duties, which in her house also meant some cleaning and milking: ‘If you can roast & boyll & help clean an House, & make up Butter, & milk two or three cows . . . & you help iron & get up ye Cloaths. If you can do these things wee will endeavour to teach you the rest of the Cookery.’66

During the course of the eighteenth century, it appears that the roles of the traditional ‘waiting gentlewomen’ and the chambermaid gradually merged to become the familiar ‘lady’s maid’, a well-presented servant who would be always in attendance on a great lady. In many cases such a personal maid would sleep in the same room, an adjoining room or even in the passage outside, and travel with her mistress from place to place.

In another book, The Servants Directory, Improved, published in 1761, Hannah Glasse outlined the duties of the traditional chambermaid, who is encouraged to ‘Take great care to know all your mistress’s method and time of doing her business; and be very punctual and acute in your attendance . . . and be sure to have all her linen well air’d and when dress’d or undress’d, fold up everything very neat.’ She focuses on cleaning the fine textiles of the day, such as silks, satins and damasks, with special instructions for cleaning flowered silks with ‘bread and power-blue . . . and if any silver or gold flowers be in it, take a piece of crimson velvet and rub the flowers’.67

The housemaid was essentially the cleaner, doing everything from making beds and mending linen to cleaning floors, doors, windows, carpets and furniture, as well as the scrubbing, cleaning and preparation of fireplaces. A housemaid’s day was gruelling. In Hannah Glasse’s book she is told to:

Be up very early in a morning, as indeed you are first wanted; lace on your stays, and pin your things very tight about you, or you never can do work well . . .

Be sure always to have very clean feet, that you may not dirty your rooms, and learn to walk softly, that you may not disturb the family. The first thing, if in winter, is to light your fires, and clean your hearths; if in summer, the stove rubbed and the dirt in your hearth swept out.

These directions continue for over a page, before the housemaid is advised to move on to locks, then carpets, curtains, windows and shutters, dusting the pictures, frames and plasterwork, before sweeping the room out.68

Hannah Glasse includes many accepted techniques for cleaning and is clearly a great believer in fresh air:

For sweeping the stairs a little wet sand is recommended on the top stair, to help keep the dust down. All this you are to get done before your mistress rises. When the family is up, go into every bed chamber, throw open all the windows to air the rooms, and uncovering the beds to sweeten and air them; besides it is good for the health to air the bedding, and s

weet to sleep in when the fresh air has had access to them, and a great help against bugs and fleas.69

Whilst scouring the house from top to bottom, housemaids were also expected to be properly modest in deportment and dress, and to be subservient, as is made clear by a note in the 1768 household book of the Duchess of Northumberland: ‘They are always to keep themselves clean & neat but not to dress above their station.’70

By the eighteenth century, the number of women servants in great country houses had swelled, and many had the most humble jobs. The former scullion, now a female scullery-maid, had to clean the kitchen and wash the cooking utensils used in the preparation of the meals – some of the most unforgiving work in the country house – as well as cleaning and preparing various foodstuffs, especially vegetables.

Hannah Glasse’s book gives the scullery-maid a messy and labour-intensive recipe for cleaning pewter, tin and copper: ‘Take a pail of wood ashes (either from the baker’s dyers or hot pressers, the latter is the best) half a pail of unslack’d lime, and four pails of soft water; boil them all in a copper together, stirring them; when they have boiled about half an hour, take it all together out of the copper into a tub, and let it stand cold, then pour off clear and bottle for use.’71

Up and Down Stairs

Up and Down Stairs