- Home

- Jeremy Musson

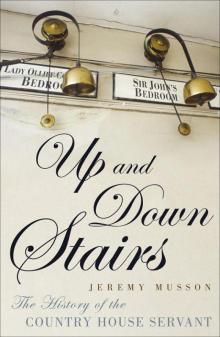

Up and Down Stairs Page 15

Up and Down Stairs Read online

Page 15

On 22 September 1736 one gentry mistress, Elizabeth Purefoy, wrote to a butcher at Brackley: ‘Mr King, I want a cook maid. If you should hear of any that are at the Statute Fair today, I shall be there by and by.’ In 1743, she petitioned a Mrs Sheppard concerning another servant: ‘I hope the maid will do if she can sew well, that is to work fine plain work as mobs and ruffles. If she comes she must bring a character [reference] of her honesty from the person she lived with last. My custom is to give the servants a shilling for the horse hire & they come themselves & I will give her half a crown because she comes so far.’2

Letters from landowners to relations and friends are peppered with references to servants looking for posts, or posts vacant. Among the unpublished letters from Nostell Priory in Yorkshire are some from Jane, Countess of Dundonald, to Sabine, Lady Wynn of Nostell, written in 1776, about engaging a Mrs McPhell on her behalf, and enclosing ‘a very ample character of the Housekeeper [who] was in Lord Kinnoul’s [Kinnoull’s] family’. As the reference was ‘very satisfactory’, she ‘ventured to give her earnest as a hir’d servant from this term of Whitsunday being the 15th of this month till the 11th of Nov[ember].’3 Lady Dundonald did as she was bid but with some hesitation, because she had not yet heard from Lady Wynn as to her requirements and the wages she was offering, but ‘if I hadn’t hired Mrs McPhell today she was to have been engaged for another family tomorrow’.

Evidently the arrangement does not work out for Lady Dundonald wrote later that year:

I’m very sorry to find Mrs [Mc]Phell the Housekeeper has behav’ed ill, and quite disappointed the hopes we had cause to entertain from the character Lady Elizabeth Hay gave of her which I transmitted to your Ladyship. Servants nowadays are so inconsistent as to behave well in one place and ill in another. Idleness, Dress and Insolence are their prevailing vices. It gives me much uneasiness that the woman has been so foolish – how happy she might have been otherwise in your service.

One longs to know the housekeeper’s side of the story.

Few such responses remain from the eighteenth century, although one servant at Hall House, near Hawkhurst in Kent, wrote bitterly handing in their notice with the following remarks: ‘I see there is no such thing as pleasing you . . . and though I cant please you, I dont doubt but I shall please other people very well. I never had the uneasiness anywhere, as I have here.’4

Lady Dundonald had also clearly played a role in hiring a French governess: ‘Do tell me my dear Lady Winn does Madame Picq please you? I am very desirous to know if she fulfils the important duties of a governess. I wish her being married be no barr to it.’ It was very unusual to hire a married governess, but the Frenchwoman seems to have given satisfaction as there is mention of Miss Wynn’s making advances in the language: ‘I’m rejoic’d that my friend Madame le Picq gives your Ladyship such satisfaction and that Miss Wynn makes surprizing progress in the French.’5

One letter early in the century, from Samuel Heathcote to the father of a young footman, sets out typical terms of engagement: ‘If your son be at liberty to come from Mr Hurts, and have his masters free Consent: I shall be willing to take him into my service on the following terms & Conditions’. This included: ‘that He serve me as a footman, or in any other Business for the term of four years.’ Clearly, in this case flexibility was a prime requirement.

The footman, or whatever else he might be, would get a certain amount of clothing from his employer, such as annually a new hat, a coat, a waistcoat, breeches, one pair of stockings and one pair of shoes, but must find the rest himself. If, at the end of the four years, he had ‘faithfully & honestly performed his Service, He shall have fifteen pounds, and shall be then free either to leave my Service or continue longer in, as We can then Agree’. The acceptance of terms, which included making up funds if his vails (or tips) fell short, was signed by both father and son.6

In contrast to this commonplace example, we should also remember that in the eighteenth century – indeed, from the late seventeenth century – many others were unable to draw on such parental protection. Young boys were brought from the West Indies, Africa or India as slaves, to become pageboys in aristocratic households. Although some were treated well and given some education, their lives must have seemed so alien as to have been utterly bewildering.

Whilst many like them were slaves by origin, sometimes they were paid wages just as if they were free. In fact, there was some confusion over their legal status right up to the point when slavery was finally abolished in Great Britain in 1833. As early as 1706, Chief Justice Holt wrote that ‘by common law no man can have a property in another’. This suggested that as soon as a slave came to England he became free, although this notion was soon squashed by Philip Yorke as Attorney-General.7

Slavery was outlawed in Scotland as early as 1778, as a result of the case of Knight versus Wedderburn. Joseph Knight had been purchased in Jamaica and brought to Scotland at the age of twelve or thirteen to be a personal servant. Eventually, Knight married and left the service of John Wedderburn, who later had him arrested. When local justices declared that Knight must continue to be a slave, the sheriff of Perthshire ruled that the state of slavery was ‘not recognized’ by the laws of Scotland, a judgment upheld by the court of session in that year.

Granville Sharp, one of the active abolitionists of the time, intervened in the case of a young slave, James Somerset, who had been shipped over to England from Virginia. He had escaped, been recaptured and put in irons. Sharp had him brought before Lord Mansfield, who ruled (eventually) for Somerset’s release, but ruling too that a slave could not be forcibly repatriated against his will.8

Curiously, Dido Belle, the child of a black slave woman and Sir John Lindsay, Lord Mansfield’s nephew, and lived in his household at Kenwood. She managed the dairy there and became a companion-servant to her cousin. Mansfield not only left her money and an annuity in his will but confirmed her status as a free person.9

Numerous young black servants, forgotten to history, can be glimpsed in portraits of the period. One such is thought to be James Cambridge, who appears in the portrait of the Earl and Countess of Burlington, which now hangs at Lismore Castle in Ireland. The fashion for the possession of a black servant may have been begun by Venetian merchants. Certainly they appear in portraits in great country houses almost as a visual foil to the whiteness and delicate complexions of the young women of the family.10

The bitter truth is that black servants were sometimes treated as little better than playthings for the aristocracy, their youth used up far away from their families. The Duchess of Kingston had a page called Sambo, whom she brought up from the age of five or six, dressing him in fine style and taking him to the theatre, where he sat in her box. Once he reached the age of eighteen or nineteen, however, she tired of him and sent him back to the West Indies.11

We must be grateful for the fact that there were always critics of this practice. As early as 1710, Richard Steele wrote a letter of complaint to The Tatler as if he himself were one such child: ‘As I am patron of persons who have no other friend to apply to, I cannot suppress the following complaint: Sir – I am a six-year old negro boy, and have, by my lady’s order, been christened by the chaplain. The good man has gone further with me, and told me a great deal of news: as I am as good as my lady herself, as I am a Christian, and many other things.’ At one point, it was erroneously believed that slaves who converted to Christianity while in England were automatically granted their freedom. The letter continued: ‘but for all this, the parrot, who came over with me from our country is as much esteemed by her as I am. Beside this, the shock dog has a collar that cost as much as mine. I desire also to know whether, now I am a Christian, I am obliged to dress like a Turke and wear a turbant. I am, sir, your most obedient servant, Pompey.’12

A memorial stone in Henbury, near Bristol, commemorates the death of a black running footman: ‘Here Lieth the body of Scipio Africanus, Negro Servant to ye Rt Hon Charles Williams, Earl of Suffo

lk and Bristol. Who died ye 21 Dec 1720 aged 18 years.’13 These high-sounding classical names suggest that black slaves were a high-status possession in a civilised society, a strange reflection on the culture that informed so much of the best literature and architecture of the day. The inscribed verse illustrates the paradoxical and confused attitude to young slaves in Britain. It begins:

I who was born a Pagan and a slave

Now Sweetly Sleep a Christian in my Grave

What tho’ my hue was dark my Savior’s sight

Shall change this darkness into radiant light.

Black pages were thought of as little more than chattels. Early in the century, a duchess wrote to her mother that her husband was unwilling that she should accept the gift of such a child from a friend and offering to pass him on in her turn: ‘Dear mama, George Hanger has sent me a Black Boy, eleven years old and very honest, the duke don’t like me having a black, and yet I cannot bear the poor wretch being ill-used; if you liked him instead of Michel I will send him; he will be a cheap servant and you will make a Christian of him and a good boy; if you don’t like him they say Lady Rockingham wants one.’14

One of the more inspiring stories was that of Ignatius Sancho, which begins in the bleak misery of British-sponsored slavery. He was born in 1729 on board a slave ship; his mother died and his father committed suicide. Ignatius was presented as a gift to three sisters in Greenwich who refused to educate him. He himself wrote years later that he had the misfortune to have been placed ‘in a family who judged ignorance the best and only security for obedience.’15 He taught himself how to read and write and attracted the attention of some of the nobility. The Duke of Montagu met him and took him ‘frequently home to the Duchess, indulged his turn for reading with presents of books, and strongly recommended to his mistresses the duty of cultivating a genius of such apparent fertility.’16

Aged around twenty, Ignatius ran away and threw himself on the mercy of the widowed Duchess of Montagu, who took him in and employed him as a butler, leaving him a legacy when she died in 1751. Ignatius later went into service, probably as a valet to the Earl of Cardigan, and turned out to be a gifted musician. He left service to become a successful grocer and corresponded with the novelist Laurence Sterne. He also married a West Indian woman who bore him six children. In The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho (1802), he wrote: ‘the latter part of my life has been . . . truly fortunate, having spent it in the service of one of the best families in the kingdom.’17 He was admired for his wit and erudition.

By 1770, 14,000–20,000 blacks were believed to be living in London, principally as a side effect of the lucrative trade between Britain and its sugar-planting and slave-holding islands in the West Indies.18 Horace Walpole recalled that the sisters of Lord Middleton had a black servant ‘who has lived with them a great many years and is remarkably sensible’. On hearing that the British were sending a ship to the Pellew Islands in the Pacific, this servant exclaimed: ‘Then there is an end of their happiness.’ Walpole remarked rightly: ‘What a satire on Europe!’19

Young children from India and China were also taken into service. The Indians were often attached to the households of men who were officers of the East India Company; they appear also to have had the status of slaves.20 In the Crimson Drawing Room at Knole hangs the remarkable portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds of Wang-y-Tong, a Chinese page employed by the 3rd Duke of Dorset and brought to England by John Bardby Blake, a schoolfellow of the duke’s and an official of the East India Company. The duke was enlightened enough to have his page educated at Sevenoaks Grammar School.21

Most landowners appear blind to the unfairness of the life of young slaves, but were ready to find fault with their freeborn counterparts. Grumbling about servants became a national pastime in the eighteenth century. In 1711, the Spectator printed a satirical exchange of letters, the first asking the journal to consider

the general corruption of Manners in the servants of Great Britain . . . I have contracted a numerous Acquaintance among the best sort of people, and have hardly found one of them happy in their servants. This is a matter of great Astonishment to Foreigners . . . especially since we cannot but observe That there is no Part of the world where servants have those Privileges and Advantages as in England: They have no where such plentiful Diet, large Wages, and indulgent liberty: There is no Place wherein they labour less, and yet where they are so little respectful, nor wast[e]ful, more negligent.

The Spectator published an arch response, blaming ‘the custom of giving Board Wages [or cash wages in lieu of being fed, when the employer was away]: ‘This one instance of false Oeconomy, is sufficient to debauch the whole Nation of Servants.’22

Dean Jonathan Swift made remorseless fun of serving men and women, as we have already seen from his trenchant views on the footman. His brilliant satire on the faults of servants of a large household was modelled on an English house but was most likely informed by his experiences in both England and Ireland. Although written in the 1730s, Directions to Servants was not published until 1745, after his death. 23

Swift deals with each member of staff in turn: butler, cook, footman, coachman, groom, housekeeper, chambermaid, waiting maid, housemaid, children’s maid, nurse, laundress, dairymaid, house steward, land steward, porter and tutoress – and thus supplies a titillating portrait of the servants of an aristocratic household. He revels especially in absurd advice:

When your master or lady call a servant by name, if that servant be not in the way, none of you are to answer, for there will be end to your drudgery, and masters themselves allow, that if a servant comes when he is called that is sufficient. . . . When you are at fault, be always pert and insolent; and behave yourself as if you were the injured person; this will immediately put your master and lady off their mettle . . .24

Never submit to stir a Finger in any Business but that for which you were particularly hired. For example, if the groom be drunk or absent, and the butler be ordered to shut the stable door, the Answer is ready, An it please your Honour, I don’t understand horses: If a corner of the hanging wants a single nail to fasten it, and the Footman be directed to tack it up, he may say, he doth not understand that sort of work, but his Honour may send for the upholsterer.25

Most memorable of all: ‘Never come till you have been called three on four times; for none but dogs will come at the first whistle: and when the master calls “Who’s there?” no servant is bound to come; for Who’s there is nobody’s name.’26

One cannot help wondering about Swift’s relationships with his own domestics, which, given his connection with ‘Stella’ – the daughter of a household servant – when he himself was a mere secretary, were probably not as clear cut as one might think. One nineteenth-century book of stories about Swift and other Irish wits contains some plausible, if anecdotal, accounts of how he treated his own staff:

Swift’s manner of entertaining his guests, and his behaviour at table, were curious. A frequent visitor thus described them: He placed himself at the head of the table, and opposite to a great pier glass, so that he could see whatever his servants did at the great marble side-board behind his chair. He was served entirely in plate, and with great elegance . . .

The beef once being over roasted, he called for the cook-maid to take it down stairs and do it less. The girl very innocently replied that she could not. ‘Why what sort of a creature are you,’ exclaimed he, ‘to commit a fault which cannot be mended?’ . . . [and observed to his neighbour] that he hoped ‘as the cook was a woman of genius, he should by this manner of arguing, be able, in about a year’s time, to convince her she had better send up the meat too little than too much done’.27

Swift also famously held a saturnalia modelled on the Roman festival in which slaves would be served by their masters, as a gesture of humility before the Roman gods, but when a manservant sent back the meat just as Swift was apt to do, it caused him to fly into a temper and chase the servants from the room. Swift himself started li

fe in the service of Sir William Temple at Moor Park in Surrey and, according to Temple’s nephew, who disliked him, he was not in those days allowed to dine with the family. This throws an interesting light on the psychology behind his satire.28

The real-life issues of the day are perhaps reflected more accurately in the letters of Elizabeth Purefoy, the mistress of Shalstone, a moderately sized establishment in Buckinghamshire. They contain numerous references to servants getting into unfortunate scrapes, either petty theft or unwanted pregnancy, such as the one for 3 May 1738: ‘’Tis not my dairy maid that is with child but my cookmaid, and it is reported our parson’s maid is also with kinchen [i.e. child] by the same person who has gone off & showed them a pair of heels for it. If you could help me to a cook maid as I may be delivered from this, it will much oblige.’29

The following year she is driven by similar circumstances to write to a Mr Coleman: ‘About 6 weeks ago, I hired one Deborah Coleman who tells me you are her father. I am sorry to tell you that she is very forward with child. She denied it and I was forced to have a midwife to search her, upon which she confessed it was so, and by Mr Launder’s manservant whom she lived with.’30 By 1743, Mrs Purefoy had become more circumspect in her hirings: ‘am obliged to you for enquiring after a maid, & if her living at home in a public house has not given her too great an assurance to live in a civilised private family, I think there will be a probability of her doing’.31 Unwanted pregnancies seen to have been a perpetual hazard for young maidservants, and then for their employers too.

Up and Down Stairs

Up and Down Stairs